Any student of economics knows from his or her money and banking course that there are two different effects that occur when you inject money into the economy. The first is called the "liquidity effect" and it operates when the money supply is increased. It operates in the short run when prices are sticky, so that no price adjustments take place. Using the diagram below, you would just increase the supply of money, hence shifting the vertical M curve to the right in the diagram below. That lowers interest rates. Of course that should lower interest rates in normal circumstances, unless you hit extremely low interest rates in which case you could find yourself on the flat portion of the L or money demand curve. In this case, as Keynes pointed out, you find yourself in a so-called "liquidity trap". In a liquidity trap, increasing money supply will not lower interest rates further, so will not stimulate the economy. We used to teach this as an academic curiosity until it occurred in Japan ( - a zero bound on interest rates), but now most monetary economists realize that it is not just a curiosity - it can happen, and it did, even in the US!!

Any student of economics knows from his or her money and banking course that there are two different effects that occur when you inject money into the economy. The first is called the "liquidity effect" and it operates when the money supply is increased. It operates in the short run when prices are sticky, so that no price adjustments take place. Using the diagram below, you would just increase the supply of money, hence shifting the vertical M curve to the right in the diagram below. That lowers interest rates. Of course that should lower interest rates in normal circumstances, unless you hit extremely low interest rates in which case you could find yourself on the flat portion of the L or money demand curve. In this case, as Keynes pointed out, you find yourself in a so-called "liquidity trap". In a liquidity trap, increasing money supply will not lower interest rates further, so will not stimulate the economy. We used to teach this as an academic curiosity until it occurred in Japan ( - a zero bound on interest rates), but now most monetary economists realize that it is not just a curiosity - it can happen, and it did, even in the US!!That is the reason why we have QE, or quantitative easing. It is a way of stimulating the economy without relying on pushing official interest rates lower. In the longer run though, prices are flexible, and they adjust to changes in the money supply, according to the quantity theory of money. The mechanism whereby this transition happens though is related to the so-called Fisher effect. The Fischer effect basically says that higher inflation rates should be reflected one for one in higher nominal interest rates. So as inflation begins to rise after a monetary injection, at some point we should see interest rates rising. Obviously though the Fisher effect only works if you have a response in inflation. At the moment, as the chart below shows, we really don't see too much response in inflation during 2013 ( - this includes the data release for August, released today, September 17th).

The key thing though is that it is really not actual inflation that matters as interest rates are a forward looking variable. The interest rate is how much you charge or are charged for lending or borrowing from now into the future. So it is really inflation expectations that are important here, as they are the equivalent forward looking variable, rather than the current level of inflation.

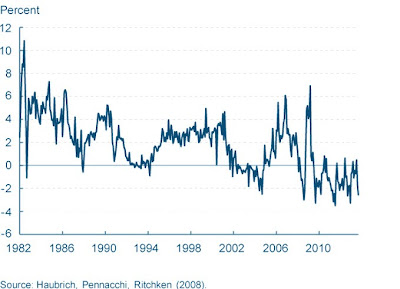

Luckily the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland has come up with some new methodology for teasing out inflation expectations from inflation swsps (a financial derivative in which investors swap a fixed payment for payments based on the CPI), which run the gamut from one to 30 years. The results of this academic work by Joseph G. Haubrich, George Pennacchi, and Peter Ritchken of the Cleveland Fed is updated every month on a special Cleveland Fed website which can be found here.

I have reproduced the current chart of Inflation expectations from the Cleveland Fed's methodology in the chart on the left. What is striking is that if we use the ten year swaps we appear to be at a turning point in terms of expectations. Inflation expectations now appear to be potentially moving up again. And that means that if 10 year bond rates are yielding just over 2.8%, that given that inflation expectations are roughly 2%, that the real interest rates, in other words the real gain lenders get from loaning their money out is around 0.8%.

I have reproduced the current chart of Inflation expectations from the Cleveland Fed's methodology in the chart on the left. What is striking is that if we use the ten year swaps we appear to be at a turning point in terms of expectations. Inflation expectations now appear to be potentially moving up again. And that means that if 10 year bond rates are yielding just over 2.8%, that given that inflation expectations are roughly 2%, that the real interest rates, in other words the real gain lenders get from loaning their money out is around 0.8%.The real interest rate is important in an economy because it signals the rewards from lending. For very short term loans these are now negative - in other words it is not worth lending short term for most banks. We can see this if we calculate the short term real interest rate - which is given as say a 2 year bond yield minus the expected inflation rate over a 2 year horizon.

Short term real rates are about -3%. This means that the Fed has really pushed short term interest rates down to an incredibly low level - well we know this already from my previous blog which you can read here.

But in terms of policy implications, and what needs to happen this week at the Fed's monetary policy meeting, is that these short term lending rates need to rise to turn the real interest rate positive again. That means that in fact the Fed should, if anything, extract much more short term credit from the market when it tapers than long term credit so as to allow short term nominal interest rates to run to more normal levels again and make it profitable to lend short term. At the moment, in one sense, the Fed's critics are right - the Fed's monetary policy is distorting the yield curve, and the sooner the Fed extricates itself from this the better.

Very interesting analysis in light of the Fed's reluctance to start to taper QE. The fact that the Fed has access to, and gives credence as a target policy variable to, changes in inflation expectations may be the key. One other way they have looked at this is via TIPS breakeven curve (as well as inflation swaps) and in particular the 5yr5yr forward rate (ie the level of 5yr inflation that the market expects to prevail in 5yrs time). When measure such as this start to accelerate the Fed may be prompted to move, and this makes much more sense rather than any slavish adherence to the level of unemployment which has always been a lagging indicator.

ReplyDelete