One of my ex-students, who is now working for a prestigious Financial Services sector company, contacted me to ask me about the US$ and tariffs and if there was any relationship between the two.

Why is this important? Well it is important for several reasons, perhaps most notably because the effects of a higher dollar actually appear to work against the objective of the Trump adminstration's trade policies of reducing trade imbalances between the US and the rest of the world. How is this the case? Well a higher dollar means that our exports appear more expensive to foreigners, but our imports then appear cheaper to domestic residents. So in fact (depending on price elasticities and what is called the Marshall Lerner condition), our exports could fall and our imports increase, which everything else remaining constant would worsen the trade deficit.

But any student of economics who has completed an intermediate macroeconomics course actually knows that there is a more fundamental macroeconomic link between trade policy and the exchange rate, which is presented in perhaps its most simplistic form in Greg Mankiw's Intermediate Macroeconomics textbook (see Chapter 6). So let's deal with the hard stuff first and tackle the macro theory. To those of you who are more "wonkish" out there, this is known as the Mundell Fleming model, which got its name from the two Canadian economists who originally constructed the model.

The idea of the chart is that there are 2 relationships which govern our external sector. The first is that our real exchange rate is related to our trade balance, and that relationship is embodied by the downward sloping curve labelled NX. The second is that our Balance of Payments must balance. This means that whatever happens on the current account, which can be mostly represented by our trade balance Net Exports = (Exports - Imports), must be matched by what happens on our Financial account, which is determined by the imbalance between our savings and our investment. So all the vertical line says is that if we have a given level of Savings (the funds available to firms) and Investment (the amount that firms need to fund their investment expenditure), then that means that this must be the amount that is made available through money flows in or out of the country. In this simplified setup, this is not dependent on the exchange rate. So in equilibrium we should be where the 2 blue lines cross, so where the current account and the financial account of the Balance of Payments match with opposite signs (so that their sum is zero and hence we are in balance - a constraint that every country has to satisfy).

So what happens when we have a change in trade policy, which is essentially what has happened with the Trump administration's imposition of tariffs and threat of imposition of tariffs ( - as financial markets react in terms of expectations of future events)?

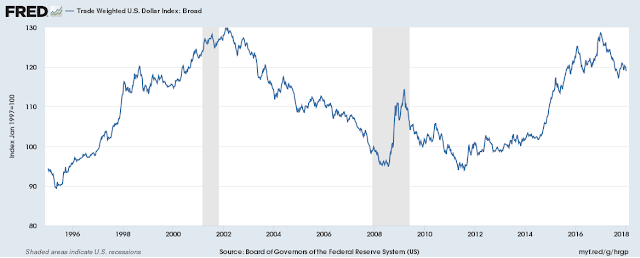

Now let's move beyond the economics here, and think about the implications for the valuation of financial assets outside of the US. I listen regularly to CNBC and there has been a lot of talk there about how emerging markets have not performed well so far this year and whether there is any likelihood of a rebound. Obviously a strong US dollar makes for foreign stocks of any type to look cheap in comparison to US stocks, and given the cyclical nature of movements in the US dollar, over the long haul it makes sense to accumulate (good) foreign stocks when the dollar is strong so that when the dollar weakens you enhance your returns by getting a double whammy return (from the stock and also from the gain in the foreign currency against the US dollar). That is one reason why, when you look at the chart above, emerging markets did very well last year as the US dollar weakening gave an extra boost to foreign stocks.

So while we have an exceptionally strong dollar as we do now, I think it is actually sensible to start accumulating good foreign stocks ( - not necessarily in emerging markets incidentally), and preferably ones that pay a secure and decent dividend so as to pay you while you wait for US dollar to do a reversal. If you have to go for an emerging market, I still suggest that India is the brightest spot right now, mostly because it still has huge potential from a growth perspective, but also because it is not in the cross-hairs of the Trump administration's trade policies.

Lastly, the next obvious question to ask is what might cause the US dollar to initiate a depreciating trend again. My first answer would obviously be some satisfactory resolution on the trade issues confronting the global economy right now. That might entail some brokered compromise or it might entail some other event that diverts the Trump administration away from its focus on trade issues.

Why is this important? Well it is important for several reasons, perhaps most notably because the effects of a higher dollar actually appear to work against the objective of the Trump adminstration's trade policies of reducing trade imbalances between the US and the rest of the world. How is this the case? Well a higher dollar means that our exports appear more expensive to foreigners, but our imports then appear cheaper to domestic residents. So in fact (depending on price elasticities and what is called the Marshall Lerner condition), our exports could fall and our imports increase, which everything else remaining constant would worsen the trade deficit.

But any student of economics who has completed an intermediate macroeconomics course actually knows that there is a more fundamental macroeconomic link between trade policy and the exchange rate, which is presented in perhaps its most simplistic form in Greg Mankiw's Intermediate Macroeconomics textbook (see Chapter 6). So let's deal with the hard stuff first and tackle the macro theory. To those of you who are more "wonkish" out there, this is known as the Mundell Fleming model, which got its name from the two Canadian economists who originally constructed the model.

The idea of the chart is that there are 2 relationships which govern our external sector. The first is that our real exchange rate is related to our trade balance, and that relationship is embodied by the downward sloping curve labelled NX. The second is that our Balance of Payments must balance. This means that whatever happens on the current account, which can be mostly represented by our trade balance Net Exports = (Exports - Imports), must be matched by what happens on our Financial account, which is determined by the imbalance between our savings and our investment. So all the vertical line says is that if we have a given level of Savings (the funds available to firms) and Investment (the amount that firms need to fund their investment expenditure), then that means that this must be the amount that is made available through money flows in or out of the country. In this simplified setup, this is not dependent on the exchange rate. So in equilibrium we should be where the 2 blue lines cross, so where the current account and the financial account of the Balance of Payments match with opposite signs (so that their sum is zero and hence we are in balance - a constraint that every country has to satisfy).

So what happens when we have a change in trade policy, which is essentially what has happened with the Trump administration's imposition of tariffs and threat of imposition of tariffs ( - as financial markets react in terms of expectations of future events)?

As you can see from the diagram from Mankiw's textbook, the theoretical implication is that imports fall as one would expect, but that leads to an imbalance on the Balance of Payments, so the exchange rate will appreciate, which in turn will choke off exports and stimulate imports, which ultimately leads us back to the same level of net exports.

President Trump is causing the US$ to appreciate simply because of his tariff talk and in some instances his tariff actions. So the flow of causation definitely runs from the threat of imposing large tariffs on our trading partners through to currency appreciation. And why is he doing this? Because his main objective is to improve the US trade imbalance. Economic theory suggests, however, that this is completely futile, as all it does is appreciate our currency and leave our trade balance at roughly the same level.

But of course this is just theory, and it relies on a raft of unrealistic assumptions. So can we glean something from the actual data? Below I have plotted real Net Exports of Goods and Services vs the Trade Weighted US dollar on the same graph, to give you an idea of how these two variables move over time. [And for those of you who say I should be using the real exchange rate (RER), the RER essentially follows almost exactly the same path as the nominal trade weighted version].

Clearly sometimes the currency and Net Exports move together, as during the "great recession" and sometimes they move in different directions, as they have done in recent years. Clearly it largely depends on what is causing the change in Net Exports, as this variable is the net result of a complex combination of different factors. Nevertheless, the sharp move upwards in the real value of the US dollar in 2015 through the beginning of 2016 has definitely been reflected by a deterioration in the Real Net Exports of goods of services. What is also clear here is that there has been a jolting rebound upwards in the exchange rate since President Trump took office, which will likely be reflected in little improvement in the Real Trade Balance of goods and services for the next while.President Trump is causing the US$ to appreciate simply because of his tariff talk and in some instances his tariff actions. So the flow of causation definitely runs from the threat of imposing large tariffs on our trading partners through to currency appreciation. And why is he doing this? Because his main objective is to improve the US trade imbalance. Economic theory suggests, however, that this is completely futile, as all it does is appreciate our currency and leave our trade balance at roughly the same level.

But of course this is just theory, and it relies on a raft of unrealistic assumptions. So can we glean something from the actual data? Below I have plotted real Net Exports of Goods and Services vs the Trade Weighted US dollar on the same graph, to give you an idea of how these two variables move over time. [And for those of you who say I should be using the real exchange rate (RER), the RER essentially follows almost exactly the same path as the nominal trade weighted version].

Now let's move beyond the economics here, and think about the implications for the valuation of financial assets outside of the US. I listen regularly to CNBC and there has been a lot of talk there about how emerging markets have not performed well so far this year and whether there is any likelihood of a rebound. Obviously a strong US dollar makes for foreign stocks of any type to look cheap in comparison to US stocks, and given the cyclical nature of movements in the US dollar, over the long haul it makes sense to accumulate (good) foreign stocks when the dollar is strong so that when the dollar weakens you enhance your returns by getting a double whammy return (from the stock and also from the gain in the foreign currency against the US dollar). That is one reason why, when you look at the chart above, emerging markets did very well last year as the US dollar weakening gave an extra boost to foreign stocks.

So while we have an exceptionally strong dollar as we do now, I think it is actually sensible to start accumulating good foreign stocks ( - not necessarily in emerging markets incidentally), and preferably ones that pay a secure and decent dividend so as to pay you while you wait for US dollar to do a reversal. If you have to go for an emerging market, I still suggest that India is the brightest spot right now, mostly because it still has huge potential from a growth perspective, but also because it is not in the cross-hairs of the Trump administration's trade policies.

Lastly, the next obvious question to ask is what might cause the US dollar to initiate a depreciating trend again. My first answer would obviously be some satisfactory resolution on the trade issues confronting the global economy right now. That might entail some brokered compromise or it might entail some other event that diverts the Trump administration away from its focus on trade issues.