On Facebook the other day a couple of my friends had signed up for a group which called for implementation of a “Robin Hood tax”. Now judging by the slick video they produced (which features Bill Nighy of Harry Potter fame, which you can see at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzZIRMXcxRc&feature=player_embedded#), this is a UK campaign (with website http://www.robinhoodtax.co.uk//) which isn’t a big surprise given the outrage of banker bonuses has been a few notches higher than in the US. The website states that among others, supporters of such a tax include the leaders of the UK, France and Germany, Lord Turner (Chair of the UK Financial Services Authority) President Zenawi of Ethiopia, Nancy Pelosi (Speaker of the US House of Congress), Joseph Stiglitz, Jeffrey Sachs, George Soros and Warren Buffet. Not exactly lightweights, so I guess we should take this proposal seriously!!

And the bankers have. Recent newspaper reports from last week (see http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/7217200/Goldman-Sachs-faces-Robin-Hood-tax-vote-rigging-claims.html) indicate that Goldman Sachs possessed one of two computers that allegedly “spammed” the internet poll with more than 4,600 “no” votes in less than 20 minutes on Thursday. And reading through some of the comments underneath the Daily Telegraph’s article, there was lots of debate, and some obviously thought what was being proposed was the same thing as a Tobin tax. Even in today’s Financial Times (see http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b8e61b16-19d0-11df-af3e-00144feab49a.html) the issue just won’t go away – with one reader calling the tax hypocritical.

So what actually is being proposed here, and isn’t it similar to the Tobin tax and therefore fraught with the same types of problems that the Tobin tax would suffer from? For those that have heard of the Tobin tax and know what it is, please jump to the next para. The Tobin tax was proposed by the Yale nobel economist, James Tobin, in 1972 so as to dampen speculative foreign exchange transactions and to raise revenue for economic development. The proposal met with derision from most economists and bankers simply because it was obvious that unless we got everyone agreeing to levy this tax, then no one would levy it. Why? Because the foreign exchange market is the largest market in the world, and although it is centred on London, it could be highly mobile in terms of where the transactions were done. So if one country didn’t participate, all the business could be done in that location, thereby circumventing the tax.

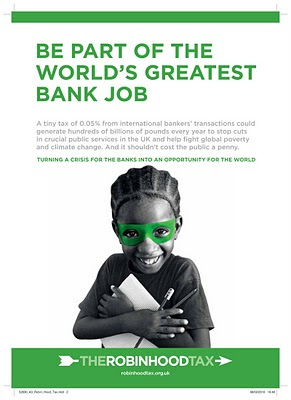

This time around we have a proposal for a financial tax on all wholesale transactions. So it would cover all financial transactions, whether foreign exchange related or not, plus it would only apply to financial institutions, and not to other multinationals, say General Electric or Walmart. The logic is that it should be levied on the financial services sector as they were the ones that caused the mess that we’re in, and it would be levied at a rate of 0.05% and generate up to £200 billion.

So, what’s wrong with it? As a concept, nothing at all. As a practical way to raise money for government, though, it would be a complete disaster. Why?

First, because the assumption here is that nothing else changes - in other words what economists term as “ceteris paribus”. Of course everything would change – bankers might still work in London, but they’d move all their business accounts offshore where they’d escape the tax. Now, you might say that 0.05% is a really small tax, and you’d be right – on a £10 (roughly $15) transfer, it would come to half a penny (or roughly three fourths of a dollar), but these amounts are not what bankers deal with – try £10 million, and even that is not large for them, and you get at least £5,000, which doesn’t look quite so small, so try a few hundred of those sizes of transactions per day, and then it becomes understandable why quite a lot of business would inevitably shift offshore.

OK, so say there is a worldwide effort to introduce a similar tax elsewhere. The second reason it wouldn’t work is simply because not everyone will agree to levy such a tax. If just one country decided not to levy the tax, then a lot of business would instantly flow to that country as it would be tax exempt. All countries know this, so there is an incentive not to get involved in the tax and so benefit from all the new incoming business.

And the third and last reason it won’t work is because if it is instituted, the bankers won’t let it work. I have worked with these people and know that the last thing they want to do is to give money to the government, for whatever reason. Also they know full well that if it is seen to work, then who knows, the government might at some point in the future need more revenue, and so will raise the tax. No, better to have it fail right at the start will be the logic, so that they don’t mess with us again. So if the bankers find that indeed they are paying this tax, they will pass it on to us the consumer. If the banks end up paying it, we the consumers will end up paying higher bank charges in one way or another. In turn I don't think consumers will like that, so if the bankers make this clear to government right from the start, will any sane government introduce such a tax?

It would all make a great script for "Yes, Minister"...if the BBC comedy were still around!!

This is a blog focusing mostly on economic cycles, macroeconomics, money and finance, with an emphasis on events in the US and Europe. Also other random thoughts on things economic and non-economic. ALL COMMENTS WELCOME.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

The Greek Tragedy Unfolds

Greece is currently waiting to hear whether a rescue package will be forthcoming from the European Union or whether it needs to go cap in hand to the IMF. Many people living outside Europe will probably think “so what?”. Indeed there are lots of cases of countries in trouble with high levels of debt, where they have gone to the IMF for help so what’s different here? I would say that Greece is different because it is also a member of the euro area and the European Union, so a default potentially threatens other highly indebted euro area member states, notably Spain and Portugal, with a much more direct link than is usually the case. The link being the fact that they all use the same money, the euro. As Paul Krugman has pointed out (see his blog at http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/02/09/anatomy-of-a-euromess/), Greece is a relatively small country so it’s debt is small but Spain is not so small and would be next on the list if contagion occurs. It’s now got so serious that the ECB is meeting tonight (2/10)by teleconference to discuss what to do ( see http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=adO.ysWPeJyQ).

What is interesting to me though is how we got into this mess ( - some people are mentioning the Olympics [see the photo above] as one obvious culprit), as well as what could and what should be done about it.

First, the European side of things. Back in 1997, Germany was getting nervous about which countries might qualify to get into Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) which was due to adopt the euro in 1999. Who would get into this “elite” club was to be decided by economic criteria that were set up as part of the Maastricht Treaty. The Maastricht Treaty (Article 103, Section 1) of 1991 clearly states that:

The Community shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of any Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project. A Member State shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of another Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project.

But Germany was afraid that the Maastricht criteria for joining the EMU was only applicable at a single point in time, and the so-called “no bailout” clause was too weak in the face of some kind of emergency in the financial markets that threatened fiscally profligate member states. So the Germans negotiated the so-called “Stability and Growth pact” (SGP) which was not incorporated into the Treaty in any subsequent revision, but was passed as a “directive” which could be revoked without having complete unanimity. In simple terms the SGP said that government budget deficits had to be below 3% of GDP unless there was a recession going on, in which case this level could be overrun on a temporary basis. If there was no recession, a long process kicks into action whereby the member state is given time to correct the situation after which non-refundable fines are levied and the proceeds shared out between the other member states. When France and Germany overran this 3% level back in 2004, a decision was made not to kick start the process, which looking back at what is now happening was a mistake, as it made the SGP completely toothless. For more on all this see my research on the SGP at http://faculty.tamucc.edu/pcrowley/Research/workingpapers.htm and go down to the SGP heading)

So, what’s happened with Greece? Well Greece has run up large debts, mostly through not having good tax collection systems in place and also through not having properly functioning public accounting mechanisms that accurately report the deficit, so that new administrations always seem to dramatically revise debt levels upwards. Only recently another €40 billion of debt was “discovered”, and to try and shrink the debt and deficit levels Greek GDP was revised upwards by including “black market” transactions into the GDP calculations. Of course the SGP doesn’t swing into action on deficit levels retroactively, only on prospective budget deficits, so Greece didn’t worry too much about sanctions under the SGP. But as my research points out, it’s a little crazy to put sanctions on a member state that has public finance problems as you’ll make things worse, not better!!

Second, what is interesting about the Greek case, is that Greece (and other highly indebted “olive” member states) have been benefitting from the low interest rates in the euro area as the area is still dominated by the big players who have lower levels of debt together with low inflation. Even with these low interest rates Greece has clearly not been able to get a grip on its public finances, so when the possibility of a creditworthiness downgrade was raised by the rating agencies, the markets sat up and took notice!

So what could be done? I would say there are 3 options:

i) Nothing. Greek debt is not that high (120% of GDP) compared to say Japanese (over 200% of GDP) and is comparable with Italian debt levels (at around 115% of GDP), so as long as Greece doesn’t default on it’s payments, who cares?

ii) Deny an EU bailout and point Greece towards the IMF. As the Maastricht Treaty states, Greek debt is Greek debt, so the Greeks need to sort out their own house.

iii) Allow an EU bailout, but with stipulations. This is the option currently under discussion, and is probably the most interesting of the options, but most problematic in my view.

The danger in i) is that if the credit rating on Greek debt is lowered, this could create contagion with other member states being next in line. That might tarnish the appeal of the euro area significantly, eventually leading to some departures from the euro area. I doubt it would lead to a collapse of the euro area as some have predicted. The danger as well with i) is that nothing happens in Greece and they have no incentive to put their public finances in order.

The second option is perhaps the most attractive from a strict interpretation of the European rulebook. The “no-bailout” clause is there for a reason, and although Greece has largely escaped scrutiny under the SGP rules, it is basically Greece’s decision about what to do. The good thing about this option is that the “conditionality” that comes with IMF loans would make it essential that Greece clears up it’s public finance mess. The danger for the euro area is the same as under i) – contagion, and nasty effects on member states that may have transparent public finances and lower levels of debt than Greece. But in the financial markets, perception is everything, so contagion cannot be ruled out, but it can't be ruled out under any of these options.

The third option is the least attractive in my judgement. There is talk of arranging some kind of bailout under Article 100, section 2 of the Treaty on European Union:

Where a Member State is in difficulties or is seriously threatened with severe difficulties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control, the Council, acting by a qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission, may grant, under certain conditions, Community financial assistance to the Member State concerned. The President of the Council shall inform the European Parliament of the decision taken.

But this would be a “generous interpretation” of the rule, as I don’t see any natural disasters or exceptional circumstances beyond the control of the Greek government. It would also set the stage for bailouts for other member states if and when there is any contagion. The “conditionality” just isn’t there either, so would not give the Greek government any incentive to clean up it’s public finances. So in my view the worst of all possible worlds, not just because it leads to so-called "moral hazard" in the future ( - who needs to worry about public finances when the SGP is toothless and you get bailed out in any case!!), but also because it obviously poses questions about the legitimacy of the European Treaty of Union if noone abides by the letter of the law.

Now there are those who are much closer to the action such as the authoritative Tony Barber of the FT (see http://blogs.ft.com/brusselsblog/2010/02/at-long-last-a-crisis-driven-big-leap-to-european-integration/) who think that this crisis will lead to the "leap forward" that European integration clearly requires if the monetary union is to be firmly entrenched within an integrated Europe, both from a fiscal point of view and a political union point of view. I doubt this. Unless the crisis becomes more widespread, and of course it might, I don't think the Greek crisis will prompt a re-think by the euro area members to press ahead with more integration in a "two-speed" set up and cede more powers to Brussels.

So in summary we got into this mess because we didn't set up a good SGP in the first place, and then secondly we didn't do the appropriate reforms to it and incorporate it into the Maastricht Treaty to give it some teeth. What should be done now? Tell Greece to go to the IMF and abide by the European Treaties otherwise what might be at risk is the entire euro area construct.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Featured Post

Free Trade on Trial - What are the Lessons for Economists?

This election season in the US there has been an extraordinary and disturbing trend at work: vilifying free trade as a "job kille...

Popular Posts

-

First, yes, I'm back again!! I now have a 18 month old baby girl, so I'm a single dad so a little limited on time these days. Neve...

-

I was at a conference recently in Tokyo, and one of the keynote speakers was Robert Engle (Nobel Prize winner in economics and Professor a...

-

This is the flag that has been carried at demonstrations lately in Athens ( - see this link if you don't believe me). It is easy to see...